-

Today in Tudor History....

27 July 1276-Death of James I of Aragon

1365-Death of Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria

1382-Death of Joanna I of Naples

1452-Birth of Ludovico Sforza, Italian son of Francesco I Sforza

1534-Chapuys to Charles V.

I received two days ago your majesty's letters of the 8th inst., since the date of which you will have learned from mine what has passed since I was at Richmond about the Queen and her servants, who after much annoyance have been released. No answer has yet been given, notwithstanding their promises, to the remonstrances I made both at Richmond and before in this town to all the Council, for all my solicitations; but they have thought better to sent it to your majesty by the resident ambassador, and the writing he has presented to you is about this. Neither has any answer been given me about leave to visit the Queen, although I have been extremely importunate for it. In this, as I mentioned in my last, they have behaved with great rudeness. It would be too long to relate the whole story; but after innumerable delays and excuses I desired Cromwell to fix an hour for me to see him upon that and other matters. He granted me 3 o'clock p. m., and at 1(“et dela à une heure”) sent me an excuse that he was summoned to Court by the King. It was only an invention, and to color it he made preparations as if to go to Court; but he only went to a house of his own half a league hence. I afterwards pressed for an audience with him three or four times, but he always excused himself. At last I wrote him the note mentioned in my last letters; and although he sent to me to say that I Should have answer from the King his master before I left to go to the Queen, and he gave me some hope that I should have leave to visit her, I had neither the one nor the other.

On the day mentioned in the said note, which was the day after my last letters, I set out with about 60 horses, both of my own men and of certain Spanish merchants here, to visit the Queen; and it happened most conveniently for my purpose that the way lay through the whole length of this town. On the second day a messenger on horseback riding at full speed went before us and returned afterwards to where I lay, accompanied by an honest man sent by the Queen's chamberlain and steward to inform me that they had received commands by the said messenger not to let me enter where the Queen was or speak with her. My answer was that I did not intend to displease the King, either in this or in anything else, but that considering the solicitations I had made to know the King's intentions in this matter, and that I had come to within five miles of where the Queen was, I would not return so lightly, until for my discharges they had either told me by word of mouth or signified it to me by letters. Next day early in the morning another man came to us of more authority than the first, being one of the old servants of the Queen, to assure me as an officer of the King that the said chamberlain and steward had express charge from the King to do that of which they had sent me word; adding on the part of the said chamberlain and steward, and on his own also, that they did not think it advisable that I should come to the house, or even pass through the village, which is but a gunshot from it, fearing that the King their master would take it ill, as the report of his refusal would be all the more confirmed and create great murmurs. To ascertain more expressly the wish of the said chamberlain and steward, I sent one of my men to them, to whom they held the same language. As my man was returning he met one of those sent by the King last year into Germany, who is a cunning fellow (un fin gallant), and was going where the Queen was. I waited all day to see if he would send to tell me anything, and also to understand meanwhile the Queen's pleasure, who sent to me to say that she held herself as well satisfied with my journey as with any service I could have done her, and was greatly bound to me for it; and as to going further to Our Lady of Walsingham, she left that to my discretion, and that she had no opportunity to write to me at Present, but would soon do so at great length. One of her chamber gave me to understand that, although she did not dare to declare it, he knew well she would have great pleasure if part of the company were to present themselves before the place; which they did next day, to the great consolation, as it seemed, of the ladies with the Queen, who spoke to them from the battlements and windows; and it seemed to the country people about that Messiah had come.

It appeared to me that if I went on to Walsingham, it would be thought I had not gone chiefly to visit the Queen, so I determined to go no further, and I sent word to the person whom the King had sent thither, that to comply with the King's wish I would not only refrain from going to the said village, but also out of regard for the same considerations I would give up my pilgrimage to Walsingham, so as to take away all matter of suspicion and not to forsake the policy I had always followed, to do all good service in my charge. The said person wished to pretend that he had not come thither by the King's order and that what the chamberlain and steward had sent to tell me was not by the King's command, as he afterwards attempted to persuade me; but at last he contradicted himself, and was obliged to confess the truth. On the return of my man, I set out to return hither by another road, in order that more people might be made acquainted with the affair, since I could not be blamed for it. The said person being informed by his spies of my departure, immediately followed me, and did not discover himself to me or any of the company until the day I was about to enter London. He then came and saluted me, and inquired if I had any commands. I begged him to tell Cromwell that I should have thought it more honorably done if the King and he had informed me of the King's intention before my removal from London, so that all the world should not have been informed of such a case, to which I could not modestly give a name, but since he has so pleased, the Queen had to thank him, seeing that the rudeness shown to her would be so notorious that it could not well be Palliated. Likewise I thought myself greatly bound to the said King that he had allowed me to give sufficient evidence that it was not my fault I had not done my duty; and that it was not necessary the said King should send more and more men to hinder me from seeing the Queen, for If I had only known that I was forbidden to do so, I would not have attempted it without knowing the King's express will, and for this cause I had written to Cromwell before my departure; and thereupon I dismissed him without further talk, although he showed some desire to converse with me; and notwithstanding that he showed himself very anxious to come and dine in this town, he stopped where I was to dine and dined with me. After dinner, besides that he wished to inform me of the two things above referred to, he said it appeared to the said chamberlain and steward that I ought not to be astonished or to take ill the refusal I had met with, which was justified by several considerations, and that if formerly, when peace and amity the most cordial prevailed between England and Spain, the English ambassadors had been refused leave to speak to the lady Joan your majesty's mother, who was the true queen of Spain, there was still more reason in these troubles to deny me an audience of the Queen. I said this argument did not proceed from the above-mentioned persons, who never had been men of the Court till now, and that they knew as little of the charge of the ambassadors of the time referred to as I did, who was a long way off, but that if he was commissioned by the King to tell me this, I might reply to him in such a fashion that he should find the truth of the proverb âMalefactum excusando facils deteriusâ. He totally denied having any commission, saying he believed firmly that the King and his Council would give me such reasons as ought to satisfy me. I replied that as to myself I was satisfied, but they would have to satisfy your majesty, and that I thought if matters were well understood apart from personal feeling, your majesty and the King his master would remain as great or better friends than you had been, for which reason I would not put myself between two such millstones by doing anything except what tended to the preservation of the amity. I therefore begged the said person to ask Cromwell what he wished me to write in this matter to your majesty, whether the simple truth, or what else. He questioned me several times what I wanted to do with the Queen. I said that was not his business, but that if the King or his Council wished to know, I would declare it willingly; and this I said, as it was a matter of great importance, in order to make the King anxious to call me about it.

I cannot imagine why the Queen has been so very urgent that I should go to her, as she has sufficient opportunities of writing or sending to me, unless it be to let all the world see, especially her wellwillers, that your majesty had [not] forgotten her, as the opposite party has given people to understand; and for this purpose I could have done nothing more to her satisfaction than what I have done, or more to the mortification of the Lady and of those who have counselled keeping me so long without an answer, though they pretend all they can not to feel it. Your majesty may judge by these things the extremity to which matters are reduced, and the truth of what the English ambassador has written as to the Queen's treatment, who is, if one can say so, more a prisoner than before, for not only is she deprived of her goods, but even a Spanish lady who has remained with her all her life, and has served her at her own expense, is forbidden to see her. It is true that in the house where she resides a great deal is spent in victuals, but as the Queen says, it is not for her servants, for she only counts five or six of them her own, and a few other ladies. The rest she considers her guards to keep her prisoner.

If we come to speak of the assistance to the landgrave of Hesse, I will act as your majesty has been pleased to write to me. The King has not been glad of the appointment of the said Landgrave, nor of the news reported from France by Rochford, among which is the delay of the interview till April, and those here say the reason is that the lady de Boulans (Anne Boleyn) wishes to be present, which is impossible on account of her condition.

The doctor of Hamburg whom those of Lubeek promised to bring here has come, and it is said the King has sent for Melanchthon and another.

The ambassadors of Lubeck and Hamburg have had much communication with the Council, who came to meet them three days ago at the house of the archbishop of Canterbury, on coming from Richmond, and gave them a great reception. It is not known yet whether they have made any treaty. I am told those of Hamburg do not draw very well with the Lubeckers. The King has laden two vessels with artillery for Ireland, and it is said he is raising 1,000 or 2,000 men on the frontier of Wales. Skeffington is not yet departed. The King is not sending thither any vessel of his own, nor has he any “de sobrez,” for with all his boasting about building ships he has only six in this river which he can use, of which he has equipped two, and one he has bought of his treasurer, and one large one which he is getting repaired. I went to see them two days ago, knowing that the King had been there in the morning on his way to Eltham to see his bastard daughter, and before he came to Eltham he sent a gentleman to make the Princess withdraw into her chamber that she might not see him.

Of late lord Dacres, who was accused of treason and detained since the peace made with the Scots, was brought to hear his sentence, and everybody expected that he would be despatched, seeing that the King had seized his goods, which are wonderfully great and equal to those of any lord in England. The Lady used her influence against him because he had always maintained the cause of the Queen and Princes. Nevertheless he defended his cause so well for seven hours that he was declared innocent by 24 lords, unanimously, and acquitted by 12 judges according to the custom of England; which is one of the most novel things that have been heard of for 100 years, for no one ever knew a man come to the point he had done and escape. And there was never seen for one day such universal joy shown in this city as there was at his liberation. The duke of Norfolk filled the Royal seat at the trial, and the ambassador of France stood by in a window in disguise; and the said Duke and the others could not dissemble about the said acquittal, fearing that if Cromwell began to lay hands on such blood, he would follow [the same course] as the Cardinal. And notwithstanding the said acquittal, the said lord Dacre, who was declared to have served the King as loyally as any lord, has been for reward shut up as much as ever, because he would not, as they say, sign a schedule by which they want him to ask pardon of the King; and this they do only to have his goods, or partly to disgust his friends and kinsmen, and also the said lords.

The Queen lately having to pay two bills of exchange from the count of Cifuentes, the one of 160 ducats supplied long before the sentence for the notaries and proctors, the other for the courier who brought the sentence, amounting to 140 ducats, has desired me to pay for the “propines” of the said sentence; and though I have several times written and told her that your majesty would have provided for it, she replies that she did not do it to spare your majesty, but considering that everything remaining in her power is in danger of being taken from her, it will please your majesty to command what is to be done with the said moneys. London, 27 July 1534.

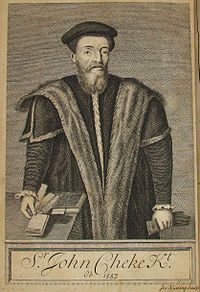

1553-Sir John Cheke was sent to the Tower for his part in putting Lady Jane Grey on the throne.