-

03 June 1535 - Sir Thomas More appears for a third interrogation in the Tower of London by Thomas Cromwell,Thomas Boleyn, Thomas Audley, and the Duke of Suffolk . He is asked to give an oath to the supremacy of Henry as head of the Church of England, but he remains silent.

Sir Thomas More.

His answers to questions put by Thomas Audeley, Lord Chancellor, and others, 3 June 27 Hen. VIII.

1. Whether he knew the statute making the King supreme head, &c. Replied that he did.

2. When asked whether the King was, as by statute decreed, head of the Church [in England] or not, he answered that "the [statute made in the Parliament] whereby the Kynges Highnes was made supreme hedd as ys aforsayd [was like unto a sword] with too edges, for yf he seyd that the same lawe werre [not] good then [yt] was daungerous to the soule. And yf he seyd contrary to the seyd estatute [then] yt was deth to the body; wherfor he would make thereto none other answer by ca[use] … old not .. f … of the shortyng of his lif."

Sir Thomas More to Margaret Roper.

Writes, as it is likely she has heard that he was before the Council this day. Perceives little difference between this time and the last. As far as he can see, the whole purpose is to drive him to say precisely one way or the other. My lord of Canterbury, my Lord Chancellor, lords Suffolk and Wiltshire, and Mr. Secretary, were here. Mr. Secretary said he had told the King about More's answer, and he was not content, but thought More had been the occasion of much grudge in the realm, and had an obstinate mind and an evil towards him, and he had sent them to command him to make a determinate answer whether he thought the statute lawful or no, and that he should either confess it lawful that the King should be Supreme Head of the Church of England, or else utter plainly his malignity. Answered that he had no malignity, and therefore could none utter, and could make no answer but what he had made before. Is sorry that the King had such an opinion of him, but comforts himself, knowing that the time shall come when God shall declare his truth towards the King. His case is such that he can have no harm, though he may have pain, "for a man may in such a case lose his head, and have no harm." Has always truly used himself, looking first upon God and next upon the King, according to the lesson his Highness taught him at first coming to his service. Can go no further and make no other answer. To this the Lord Chancellor and Secretary said that the King might by his laws compel him to give an answer. Said this seemed hard, if his conscience were against it, to compel him to speak either to the loss of his soul or the destruction of his body. Mr. Secretary referred to More's having compelled heretics to answer whether they believed the Pope to be Head of the Church or not, and asked why the King should not similarly compel him? Replied that there was a difference between what was taken for an undoubted thing throughout Christendom, and a thing that was merely agreed in this realm, and the contrary taken for truth elsewhere. Mr. Secretary answered that they were as well burned for denying that, as they were beheaded for denying this, and therefore as good reason to compel men to answer one as the other. Answered that a man is not so bound in conscience by a law of one realm as by a law of Christendom; the reasonableness or unreasonableness of binding a man to answer stands not in the difference between heading and burning, but in the difference between heading and hell. In conclusion they offered him an oath to answer truly what was asked him on the King's behalf concerning his person. Said he never purposed to swear any book oath while he lived. They said he was very obstinate to refuse that, for every man does it in the Star Chamber and elsewhere. Replied that he could well conjecture what would be part of his interrogatories, and it was as well to refuse them at first as afterward. The interrogatories were then shown him, and they were two;—whether he had seen the statute, and whether he thought it a lawful made statute or not. Refused the oath, and said he had already confessed the first and would not answer the second. Was thereupon sent away. In the communication before, it was said that it was marvel that the stuck so much in his conscience while he was not sure therein. Said he was sure that his own conscience might very well stand with his own salvation. It was also said to him that if he had as soon be out of the world as in it, why did he not speak plain out against the statute; it was clear that he was not content to die, though he said so. Answered that he has not been a man of such holy living that he might be bold to offer himself for death, lest God, for his presumption, might suffer him to fall. In conclusion, Mr. Secretary said he liked him worse than the last time, for them he pitied him, but now he thought he meant not well. God knows he means well. Wishes his friends to be of good cheer and pray for him.

1535 - Thomas Cromwell ordered all bishops to preach in support of the royal supremacy and to remove all references to the Pope from mass books and other church books.

source:http://www.onthisdayintudorhistory.com/,http://www.british-history.ac.uk/

-

2 June 1418-Death of Catherine of Lancaster,Queen of Castile as the wife of King Henry III of Castile.

Queen Catherine was the daughter of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, and his second wife, Constance of Castile (the daughter and heir of King Peter of Castile, who died at the hands of his half brother Henry II).

1510-Birth of Lady Mary Brandon, Baroness Monteagle.She was an English noblewoman, and the daughter of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, by his second wife, Anne Browne. Mary was the wife of Thomas Stanley, 2nd Baron Monteagle, by whom she had six children.Mary Brandon was a lady-in-waiting to Queen consort Jane Seymour

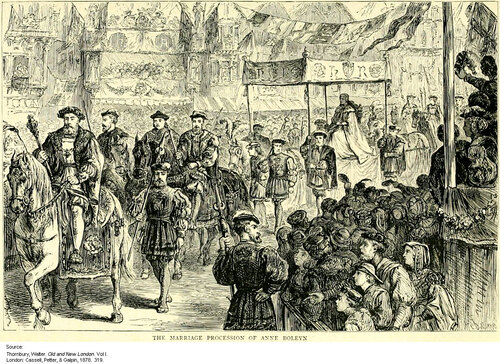

1533-Coronation Of Anne Boleyn.

Narrative of the entry and coronation of Anne Boleyn, queen of England, at London, 2 June 1533.

The Queen left Greenwich on Thursday, about four o'clock in the afternoon, in a "barque raze," like a brigantine, which was painted with her colours outside, with many banners. Her ladies attended her. She was accompanied by 100 or 120 similar vessels, also garnished with banners and standards. They were fitted out with small masts, to which was attached a great quantity of rigging, as on large ships ; the rigging being adorned with small flags of taffeta, and, by the writer's advice, with "or clinquant," as it reflects the sun's rays. There were many drums, trumpets, flutes, and hantbois. They arrived in less than half an hour at the Tower of London, where the cannon fired a salute. It was a very beautiful sight ; for, besides the vessels, there were more than 200 small boats, which brought up the near. The whole river was covered. On Friday the Queen did not leave her lodging. On Saturday, about five o'clock in the afternoon, in her royal dresses, which are of the same fashion as those of France, she mounted a litter covered inside and out with white satin. Over her was borne a canopy of cloth of gold. Then followed twelve ladies on hackneys, all clothed in cloth of gold. Next came a chariot covered with the same cloth, and containing only the duchess of Norfolk, step-mother of the Duke, and the Queen's mother. Next, twelve young ladies on horseback, arrayed in crimson velvet. Next, three gilded coaches, in which were many young ladies ; and, lastly, twenty or thirty others on horseback, in black velvet. Around the litter were the duke of Suffolk, that day Constable, and my lord William [Howard], who was Great Marshal and Great Chamberlain,—a hereditary office,—in place of his brother the duke of Norfolk. Before them marched two men, called esquires, who wore bonnets furred with ermines, somewhat like the chief usher of Paris. Then came the French ambassador, accompanied by the archbishop of Canterbury ; then the Venetian ambassador, accompanied by the Chancellor ; then many bishops, and the rest of the great lords and gentlemen of the realm, to the number of 200 or 300. Before all, marched the French merchants, in violet velvet, [each] wearing one sleeve of the Queen's colours ; their horses being caparisoned in violet taffeta with white crosses. In all open places (carrefours) were scaffolds, on which mysteries were played ; and fountains poured forth wine. Along the streets all the merchants were stationed. The Queen alighted in a great hall, in which was a high place, where she partook of wine, and then retired to her chamber.

On Sunday morning, accompanied by all the said lords and gentlemen, she went on foot from her lodging to the church, the whole of the road being covered with cloth, and being about the length of the garden of Chantilly. All the bishops and abbots went to meet her, and conducted her to the church. After hearing mass, she mounted upon a platform before the great altar, covered with red cloth. The place where she was seated, which was elevated on two steps, was covered with tapestry. She remained there during the service, after being crowned by the archbishop of Canterbury, who delivered the crown to her, and consecrated her in front of the high altar. That day the duke of Suffolk was Grand Master, and constantly stood near the Queen with a large white rod in his hand. My lord William and the Great Chamberlain were also near her. Behind her were many ladies, duchesses, and countesses, attired in scarlet, in cloaks furred with ermines —such as are usually worn by duchesses and countesses,—and in bonnets. The dukes, earls, and knights were likewise clothed in scarlet robes, furred with ermines, like the first presidents of Paris, with their hoods. The coronation over, the Queen was led back again with the same company as she came, excepting some bishops, into a great hall, which had been prepared for her to dine in. The table was very long, and the Archbishop was seated a considerable distance from her. She had at her feet two ladies, seated under the table to serve her secretly with what she might need ; and two others near her, one on each side, often raised a great linen cloth to hide her from view, when she wished "s'ayser en quelque chose." Her dinner lasted a long time, and was very honorably served. Around her was an inclosure, into which none entered but those deputed to serve, who were the greatest personages of the realm, and chiefly those who served "de sommelliers d'eschançonnerie et panetrie." The hall being very large, and good order kept, there was no crowding. Beneath the inclosure were four great tables, extending the length of the hall. At the first were seated those of the realm who have charge of the doors ; below them, at the same table, were many gentlemen ; at the second table, the archbishops, bishops, the Chancellor, and many lords and knights. The two other tables were at the other side of the hall : "à celle du hault bout" was the mayor of London, accompanied by the sheriffs ; at the other were duchesses, countesses, and ladies. The duke of Suffolk was gorgeously arrayed with many stones and pearls, and rode up and down the hall and around the tables, upon a courser caparisoned in crimson velvet ; as also did my lord William, who presided over the serving, and kept order : they were always bareheaded, as you know is the custom of this country. The King stationed himself in a place which he had had made, and from which he could see without being seen ; the ambassadors of France and Venice were with him. At the hall door were conduits pouring out wine ; and there were kitchens to give viands to all comers, the consumption of which was enormous. Trumpets and hautbois sounded at each course, and heralds cried "largesse." Next day a tourney took place, eight against eight, and every one ran six courses. My lord William led one band, and Master Carew, the grand esquire, the other.

Extracts from a manuscript account unfavorable to Anne. Though it was customary to kneel, uncover, and cry "God save the King, God save the Queen," whenever they appeared in public, no one in London or the suburbs, not even women and children, did so on this occasion. One of the Queen's servants told the mayor to command the people to make the customary shouts, and was answered that he could not command people's hearts, and that even the King could not make them do so. Her fool, who has been to Jerusalem and speaks several languages, seeing the little honor they showed to her, cried out, "I think you have all scurvy heads, and dare not uncover." Her dress was covered with tongues pierced with nails, to show the treatment which those who spoke against her might expect. Her car was so low that the ears of the last mule appeared to those who stood behind to belong to her. The letters H. A. were painted in several places, for Henry and Anne, but were laughed at by many. The crown became her very ill, and a wart disfigured her very much. She wore a violet velvet mantle, with a high ruff (goulgiel) of gold thread and pearls, which concealed a swelling she has, resembling goître. She was crowned by Cranmer, who is called "one of the judges of Susanna," and "le pape patriarche." Eighteen knights of the Bath were created. The presents to the various officers of the court cost them 200l. The duchess of Norfolk, daughter of the duke of Buckingham, would not appear at the ceremony, from the love she bore to the previous Queen, although she was Anne's aunt. The French ambassador and his suite were insulted by the people, who called him "Orson queneve, France dogue" (whoreson knave, French dog)

From a catalogue of papers at Brussels, now lost.

1535-Birth of Leo XI

1536 - Jane Seymour’s first appearance as Queen.

1537 - Executions of rebels Sir Francis Bigod, George Lumley and Sir Thomas Percy after Bigod’s Rebellion.Bigod's Rebellion of January 1537 was an armed rebellion by English Roman Catholics in Cumberland and Westmorland against King Henry VIII of England and the English Parliament. It was led by Sir Francis Bigod, of Settrington in the North Riding of Yorkshire.

1538-Hutton to Wriothesley.

Copy of a letter of the same date to Cromwell sent by the bearer, as follows:—

Received, 31 May his Lordship's letters dated the 26th. The Queen was then with the duchess of Milan in the forest of Soin. On their return to Court repaired thither. Describes his interview with the Queen. Said it was much marvelled at that the Emperor, who had made the first overtures touching the duchess of Milan, had now become so cold, that his ambassadors in England had no instructions to conclude anything, and that he (Hutton) was sorry for it, as he had hoped that such an alliance would revive the old friendship between England and the house of Burgundy. Asked her to use her influence. She said she would write to the Emperor about it, and knew no reason for his slackness unless it were his much business for this meeting. It was then about six o'clock, and the Queen departed to supper, and Hutton to his lodging. Thither came lord Benedik Court, one of the chief about the Duchess, to sup with him, and asked whether Hutton had brought the Queen any good news concerning the Duchess, saying that he prayed God he might live to see her bestowed upon the King, but there was one doubt in the matter. Asked what that was. He said as the Duchess was near kinswoman to the lady Katharine, whom the King had married, the Pope's dispensation was necessary. Replied that he did not know what might be the bishop of Rome's laws, but he was sure the King would do nothing against God's laws. Thanks for his exhortation to spare no expenses, and indeed the custom here is for lords and gentlemen to come to dinner and supper unbidden. Wrote asking his Lordship to write to John de la Dique, a procurar in the Chancery of Brabant, who has certain books and writings of Mr. Hacket's, to deliver them to Hutton; which he promises to do upon Cromwell's letter. They will be very useful to Hutton. Has wasted nothing in gaming or the like, but has spent all that he has spent to the King's honour.

1546-Prince Edward to Henry VIII.

Has not written for a long time because, seeing the King much troubled (perturbari) with warlike affairs, he scrupled to trouble him with childish letters. But now, since the mind after long labour seeks recreation, he hopes that they will prove a recreation rather than a trouble. As the King is a loving and kind father, and he hopes to be an obedient son, he thinks that they will be taken in good part. Desires his Majesty's blessing, and wishes him a good issue in all his affairs. Hunsdon, 2 June 1546.

1553 - King Edward gives approval to Cranmer's 42 Articles of Faith

1572-Execution of Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk.He was the son of the poet Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. He was taught as a child by John Foxe, the Protestant martyrologist, who remained a lifelong recipient of Norfolk's patronage. His father predeceased his grandfather, so Norfolk inherited the Dukedom of Norfolk upon the death of his grandfather, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk in 1554.He was the second cousin of Queen Elizabeth I through her maternal grandmother, Lady Elizabeth Howard.

1581-Execution of James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton He was the last of the four regents of Scotland during the minority of King James VI. He was in some ways the most successful of the four, since he won the civil war that had been dragging on with the supporters of the exiled Mary, Queen of Scots. However, he came to an unfortunate end, executed by means of the Maiden, a primitive guillotine, which he himself was said to have introduced to Scotland.

source:http://www.thetudormonarch.com/,wikipedia,http://www.british-history.ac.uk/

-

1st June 1533 - Coronation of Queen Anne Boleyn

The manner of attendance of the judges at the coronation of queen Anne, at Whitsuntide, 25 Hen. VIII., as reported by Sir John Spillman, one of the King's justices, then present.

Before the coronation, Westminster Hall was prepared, and the Court of King's Bench was kept for the time in the Exchequer Chamber, the Common Pleas in the Abbey, and the Chancery in the White Hall. The King sent letters missives to each of the justices to attend at the Coronation. On Thursday the Queen came from Greenwich to the Tower, where she rested all the Friday. On Thursday the Chancellor wrote to the Chief Justice, desiring him and his companions, in their scarlet robes, to come to Tower Hill, each with one servant, between one and two on Friday, to ride with the Queen, between the lords and knights, to Westminster Hall, and to attend at the Hall on Whitsunday at seven. When the chief justice, FitzJames, received this letter, he summoned the chief baron, Sir Robt. Norwich, chief justice of the Common Pleas, Sir Ric. Lyster, chief baron, Sir Humphrey Conisby, Sir Ant. Fitzherbert, Sir John Port, Sir Thos. Englefield, Sir John Shelley, and Sir John Spilman, who determined to ride together to the Tower. On Saturday, after dinner, they rode to the Tower on horses and mules, in scarlet gowns and hoods, sarcenet tippets and collars of S.S. ; but being too late to go into the Tower they came back to Sir John Dancy's house in Mark Lane, and after resting half an hour rode back to Tower Hill, where they staid an hour, while the knights and squires rode by. The heralds appointed the justices to ride before the knights of the Bath, of whom 18 were made that day, and before the King's council. At Westminster Hall they alighted, and waited for the Queen in the Hall next to the said knights. When she had sat in her chair and drunk, she went to her chamber, and the justices all kneeled to her ; to whom she said, "I thank you for all the honor you have done to me this day." After this they came to their inns. On Whit Sunday, wearing their coifs, scarlet robes, hoods, cloaks, and collars, they rode to Westminster Hall, and accompanied the Queen to the church in the same order as before. In the church they were with the lords upon a scaffold. When the Queen was ascended unto the high place, they and the lords descended to the door of the Hall, and put off their coifs, cloaks, and hoods, and put on their tippets, collars, and hoods, as before. The marshals assigned them to sit next to the barons, at the same table. After dinner they advanced themselves before the Queen as she went to her chamber, and kneeled down, when she spoke as before. They then came back to their inns. They were not at the jousts the next day, for they were not commanded to be present.

1536-Princess Mary to Henry VIII.

Begs as humbly as child can for his daily blessing—her chief desire in this world. Acknowledges all her offences since she had first discretion to offend till this hour, and begs forgiveness. Will submit to him in all things next to God, "humbly beseeching your Highness to consider that I am but a woman, and your child, who hath committed her soul only to God, and her body to be ordered in this world as it shall stand with your pleasure." Rejoices to hear of the marriage between his Grace and the Queen now being. Desires leave to wait upon the latter and do her Grace service. Trusts to Henry's mercy to come into his presence. As he has always shown pity, "as much or more than any prince christened," hopes he will show it to his humble and obedient daughter. Prays God to send him a prince. Hounsdon, 1 June.

Jean de Ponte to Cromwell.

"Juste deprecantibus nichil denegari debet, 1536."—On the 1st June, dined with the vicar of Honniton and another priest, at the house of John Bould, the "Lion," at Dover. There were also present a man named Granger, and the wives of Mr. Nedersolle, Mr. Wrake, and John [Bould]. During dinner a servant of the master of the Maison Dieu, named Tra[sse], came in with news that the day before Madame Anne was beheaded, the tapers at the sepulchre of queen Katharine lighted of themselves, and, after matins, at Deo Gratias, went out; that the King sent 30 men to the abbey where queen Katharine was buried to inquire about it, and the light continued from day to day; that orders would soon be issued to pray for queen Katharine as before, and afterwards a heap of heretics and new inventions would be hanged and burnt, "comme moy qui etoyt ung heretike plus grant de Angletayre, et ung false kenayve que je toys . . . . . . . . . davant que fut gayres je seroys davant le conseyll du Roy, comme ung false kanave que j[etoys];" and that I should mark well what he said. I asked whether he had heard me preach or speak heresy. He said yes, and that I had eaten milk, butter, and eggs. I said I never ate eggs. Then he said I was a false French knave, and should be had before the Council. "De Ponte," 1 June.

P. S.—I shall be killed of them of the Maison Dieu, and dare not abide in the chapel. I would not leave without permission of my friends, but I had rather leave than be killed without deserving it.

Poem descriptive of the life of Anne Boleyn, composed at London, 1 June 1536.

Speaks of her having first left this country when Mary went to France "to accomplish the alliance of the two Kings." She learned the language from ladies of honor. After Mary's return to England she was retained by Claude and became so accomplished that you would never have thought her an English, but a French woman. She learned to sing and dance, to play the lute and other instruments, and to order her discourse wisely (et ses propos sagement adjancer). She was beautiful and of an elegant figure, and still more attractive in her eyes, which invited to conversation, &c. On her return her eyes fascinated Henry, who made her, first a marchioness, and afterwards Queen, 1 June 1533. Describes the birth and baptism of Elizabeth, the establishment of the royal supremacy, and the death of More and the Carthusians, of which Anne was accused of being the cause. Hence a severe ordinance was issued against any that spoke ill of her; which shut people's mouths when they knew what ought not to be concealed. Meanwhile queen Katharine suffered patiently her degradation and even being separated from her daughter. Anne, on the other hand, had her way in all things; she could go where she pleased, and if perhaps taken with the love of some favored person, she could treat her friends according to her pleasure, owing to the ordinance. But that law could not secure to her lasting friendships, and the King daily cooled in his affection. Anne met with divers ominous occurrences that presaged evil;—first a fire in her chamber, then the King had a fall from horseback which it was thought would prove fatal, and caused her to give premature birth to a dead son. Nevertheless she did not leave off her evil conversation, which at length brought her to shame.

A lord of the Privy Council seeing clear evidence that his sister loved certain persons with a dishonorable love, admonished her fraternally. She acknowledged her offence, but said it was little in her case in comparison with that of the Queen, as he might ascertain from Mark [Smeaton], declaring that she was guilty of incest with her own brother. The brother did not know what to do on this intelligence, and took counsel with two friends of the King, with whom he went to the King himself and one reported it in the name of all three. The King was astonished, and his color changed at the revelation, but he thanked the gentlemen. The Queen, meanwhile, took her pleasure unconscious of the discovery, seeing dogs and animals that day fight in a park. In the evening there was a ball, and the King treated her as if he knew no cause of displeasure. But Mark was then in prison and was forced to answer the accusation against him. Without being tortured he deliberately said that the Queen had three times yielded to his passion. The King was thus convinced, but made no show of it, and gave himself up to enjoyment. Especially on the 1 May, he got up a tournay with several combatants; among others, my lord of Rocheford, the Queen's brother, showed his skill in breaking lances and vaulting on horseback. Norris, also, best loved of the King, presented himself well armed, but his horse refused the lists and turned away as if conscious of the impending calamity to his master. The King seeing this, presented Norris with his own horse; who, however, knew that he could not keep it long. He, Waston (Weston), and Barton (Brereton) did great feats of arms, and the King showed them great kindness "dissimulant leur ruyne prochaine." The Queen looked on from a high place, "et souvent envoioit les doulz regards," to encourage the combatants, who knew nothing of their danger. Immediately after the tournay archers were ordered to arrest Norris, and were much astonished and grieved, considering his virtue and intimacy with the King, that he should have committed disloyalty. Before he went to prison the King desired to speak to him, offering to spare his life and goods, although he was guilty, if he would tell him the truth. But being told the accusation, Norris offered to maintain the contrary with his body in any place. He was accordingly sent to the Tower. The Queen was conducted thither next day by the duke of Norfolk, and her brother also, who said he had well merited his fate. Waston and Barton followed, and pages also. The city rejoiced on hearing the report, hoping that the Princess would be restored. The whole town awaited her coming with delight.

"Et n'eussiez veu jusque aux petis enfans

Que tous chantans et d'aise triumphans.

n'y a cueur si triste qui ne rye

En attendant la princesse Marie."

But she did not remove from her lodging, and did not avenge herself by blaming the Queen when she heard that she was a prisoner; but only wished she had behaved better to the King, and hoped God would help her, adding:—

"Et si sa fille est au Roy, je promectz

Qu'a mon pouvoir ne luy fauldray jamais."

Here follows a eulogy of the Princess, describing her education in astronomy, mathematics, logic, morals, politics, Latin, Greek, &c. The expectation that she would be restored made the King apprehensive of some commotion; to appease which he caused his thanks to be conveyed to the people for their good will to him and his daughter, but told them they need not be anxious about her return, for they would shortly be satisfied. The joy of the people on this was converted into sorrow and they dispersed (et confuz s'en partit).

The Queen, meanwhile, having no further hope in this world, would confess nothing.

"Riens ne confesse, et ne resiste fort Comme voulant presque estre délivre De vivre icy, pour aulz cieulz aller vivre; Et l'espoir tant en icelle surmonte, Que de la mort ne tient plus aucun compte."

But she did not give up her greatness, but spoke to the lords as a mistress. Those who came to interrogate were astonished. They afterwards went to Rochford, who said he knew that death awaited him and would say the truth, but raising his eyes to Heaven denied the accusations against him. They next went to Norris, Waston, and Barton, who all likewise refused to confess, except Mark, who had done so already. The King ordered the trial at Westminster, which was held after the manner of the country.

Description of the process of indictment and how the archers of the guard turn the back [of the axe] (fn. 4) to the prisoners in going, but after sentence of guilty the edge is turned towards their faces; the trial at Westminster; the verdict; whereupon suddenly the axe was turned towards them; and the sentence. Everyone was moved at their misfortune, especially at the case of Waston, who was young and of old lineage and high accomplishments; but no one dared plead for him, except his mother, who, oppressed with grief, petitioned the King, and his wife, who offered rents and goods for his deliverance. But the King was determined the sentence should be carried out. If money could have availed, the fine would have been 100,000 crowns.

Rochford was not tried at Westminster, but at the Tower, with the Queen. His calm behaviour, and good defence. More himself did not reply better. The judges at first were of different opinions, but at last one view overturned the other and they were unanimous. The duke of Norfolk as president, though maternal uncle of the accused, asked them if he was guilty or not, and one replied guilty. Rochford then merely requested the judges that they would ask the King to pay his debts. The Queen then was summoned by an usher. She seemed unmoved as a stock, and came away with her young ladies, not as one who had to defend her cause but with the bearing of one coming to great honor. She returned the salutations of the lords with her accustomed politeness, and took her seat. She defended herself soberly against the charges, her face saying more for her than her words; for she said little, but no one to look at her would have thought her guilty. In the end the judges said she must resign her crown to their hands; which she did at once without resistance, but protested she had never misconducted herself towards the King. She was then degraded from all her titles,—countess, marchioness, and princess, which she said she gave up willingly to the King who had conferred them. Sentence of death, either by sword or fire, at the pleasure of the King, was pronounced by Norfolk. Her face did not change, but she appealed to God whether the sentence was deserved; then turning to the judges, said she would not dispute with them, but believed there was some other reason for which she was condemned than the cause alleged, of which her conscience acquitted her, as she had always been faithful to the King. But she did not say this to preserve her life, for she was quite prepared to die. Her speech made even her bitterest enemies pity her.

Meanwhile the prisoners prepared to die and took the Sacrament. Description of the execution of Rochford, with his dying speech, not unlike the version given in No. 1107. The other four said nothing, as if they had commissioned Rochford to speak for them, except Mark, who persisted in what he said that he was justly punished for his misdeeds.

The Queen, in expectation of her last day, took the Sacrament. Then the day of her death was announced to her, at which she was more joyful than before. She asked about the patience shown by her brother and the others; but when told that Mark confessed that he had merited his death, her face changed somewhat. "Did he not exonerate me," she said, "before he died, of the public infamy he laid on me? Alas! I fear his soul will suffer for it."

Next day, expecting her end, she desired that no one would trouble her devotions that morning. But when the appointed hour passed she was disappointed,—not that she desired death, but thought herself prepared to die and feared that delay would weaken her. She, however, consoled her ladies several times, telling them that was not a thing to be regretted by Christians, and she hoped to be quit of all unhappiness, with various other good counsels. When the captain came to tell her the hour approached and that she should make ready, she bade him for his part see to acquit himself of his charge, for she had been long prepared. So she went to the place of execution with an untroubled countenance. Her face and complexion never were so beautiful. She gracefully addressed the people from the scaffold with a voice somewhat overcome by weakness, but which gathered strength as she went on. She begged her hearers to forgive her if she had not used them all with becoming gentleness, and asked for their prayers. It was needless, she said, to relate why she was there, but she prayed the Judge of all the world to have compassion on those who had condemned her, and she begged them to pray for the King, in whom she had always found great kindness, fear of God, and love of his subjects. The spectators could not refrain from tears. She herself having put off her white collar and hood that the blow might not be impeded, knelt, and said several times "O Christ, receive my spirit !"

One of her ladies in tears came forward to do the last office and cover her face with a linen cloth. The executioner then, himself distressed, divided her neck at a blow. The head and body were taken up by the ladies, whom you would have thought bereft of their souls, such was their weakness; but fearing to let their mistress be touched by unworthy hands, forced themselves to do so. Half dead themselves, they carried the body, wrapped in a white covering, to the place of burial within the Tower. Her brother was buried beside her, Weston and Norris after them. Barton and Mark also were buried together (en ung couble).

The ladies were then as sheep without a shepherd, but it will not be long before they meet with their former treatment, because already the King has taken a fancy to a choice lady. And hereby, Monseigneur, is accomplished a great part of a certain prophecy which is believed to be true, because nothing notable has happened which it has not foretold. Other great things yet are predicted of which the people are assured. If I see them take place I will let you know, for never were such news. People say it is the year of marvels.

1540-Sir George Carew was imprisoned in the Tower or his implication in the Lisle conspiracy.

1563 - Birth of Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury,English administrator and politician.

1583 - Death of George Carew.He was the third son of Sir Edmund Carew. He graduated B.A. at Broadgates Hall, Oxford in 1522.

Carew was archdeacon of Totnes from 1534 to 1549, becoming canon of Exeter in 1535 and precentor of Exeter in 1549, and was archdeacon of Exeter from 1556 to 1569. He was dean of Bristol from 5 November 1552, but he was ejected in 1553 under Mary I. He resumed the post on the accession of Elizabeth I, and filled it until 1571. He was also dean of Christ Church, Oxford from 1559 to 1661, dean and canon of Windsor from 1560 to 1577 and dean of Exeter in 1571 to 1583

source:http://www.british-history.ac.uk/,wikipedia

-

31 May 1443 – Birth of Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby.She was the mother of King Henry VII and paternal grandmother of King Henry VIII of England. She was a key figure in the Wars of the Roses and an influential matriarch of the House of Tudor. She founded two prominent Cambridge Colleges; Christ's College in 1505, and St John's College in 1511.

1495-Death of Cecily Neville, Duchess of York ,wife of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York and the mother of two Kings:Edward IV and Richard III.

1514-Henry VIII. to Wolsey

"Has spoken to the Duke [of Longueville], who "was as ill afraid, as ever he was in his life, lest no good effect should come to pass" touching the treaty. The King expressed his willingness to come to terms if reasonable offers be made to him. He stipulated that Louis (considering how much of Henry's inheritance he withholds and how much Henry's amity may help "his matter in Italy") should pay 100,000 cr. yearly and that the amity should be made during their lives and one year after; which amity once granted, the alliance of marriage will not be refused."

Princess Mary (sister of Henry VIII)

A minute, in Fox's hand, of an agreement on the part of the King of France to receive jewellery and furniture to the value of 200,000 crowns, as the dowry of the Princess Mary, reserving certain conditions as to their restoration.

1529-The legatine court called by the Pope formally opens in the parliament chamber of Blackfriars.

Clement VIII to Henry VIII

Stephen Gardiner and Francis Bryan will testify his desire to oblige the King. The King cannot doubt of his affection and his gratitude for his services to the See Apostolic, but he cannot proceed as the King desires without grave reproach. Refers him to Campeggio. Rome, 31 May 1529

1533 – Anne Boleyn’s coronation procession through the streets of London, from the Tower of London to Westminster Abbey.

"On Thursday, 29 May 1533, 25 Hen. VIII., the lady Anne marchioness of Pembroke was received at Greenwich, and conveyed to the Tower of London, and thence to Westminster, where she was crowned queen of England.

Order was taken by the King and his Council for all the Lords spiritual and temporal to be in the barge before Greenwich at 3 p.m., and give their attendance till the Queen took her barge. The mayor of London, Stephen Pecocke, haberdasher, had 48 barges in attendance richly decked with arras, hung with banners and with pennons of the arms of the crafts in fine gold, and having in them trumpets, shallands, and minstrels ; also every barge decked with ordnance of guns, "the won to heill the other troumfettly as the tyme dyd require." Also there was the bachelor's barge sumptuously decked, and divers foists with great shot of ordnance, which went before all the barges. Order given that when her Grace's barge came "anontes" Wapping mills, knowledge should be given to the Tower to begin to shoot their ordnance. Commandment given to Sir Will. Vinstonne (Kingston), constable of the Tower, and Sir Edw. Wallsyngham, lieutenant of the Tower, to keep a space free for her landing. It was marvellous sight how the barges kept such good order and space between them that every man could see the decking and garnishing of each, "and how the banars and penanntes of armis of their craftes, the which were beaten of fyne gould, yllastring so goodly agaynste the sonne, and allso the standardes, stremares of the conisaunsys and devisis ventylyng with the wynd, allso the trompettes blowyng, shallmes and mistrielles playng, the which war a ryght symtivis and a tryhumfantt syght to se and to heare all the way as they paste upon the water, to her the sayd marvelles swett armone of the sayd ynstermentes, the which soundes to be a thinge of a nother world. This and this order hir Grace pasyng till she came a nontt Rattlyffe."

The Queen was "hallsyd with gones forth of the shippes" on every side, which could not well be numbered, especially at Ratcliffe. When she came over against Wapping mills the Tower "lousyd their ordinaunce" most triumphantly, shooting four guns at once.

At her landing, a long lane was made among the people to the King's bridge at the entrance of the Tower. She was received on coming out of her barge by Sir Edw. Walsingham, lieutenant of the Tower, and Sir Will. Kinston, constable of the Tower. The officers of arms gave their attendance ; viz., Sir Thos. Writhe, Garter king-of-arms, Clarencieux and Norroy kings-of-arms, Carlisle, Richmond, Windsor, Lancaster, York, and Chester heralds ; the old duchess of Norfolk bearing her train ; the lord Borworth (sic), chamberlain to her Grace, supporting it, &c. A little further on she was received by lord Sandes, the King's chamberlain, lord Hause (Hussey), chamberlain with the Princess, the lord Windsor, the lord Nordunt (Mordaunt?), and others ; afterwards by the bishops of Winchester and London, the earl of Oxford, chamberlain of England, lord Will. Haworth, marshal of England, as deputy to his brother Thos. duke of Norfolk, the earl of Essex, &c.

Somewhat within the Tower she was received by the King, who laid his hands on both her sides, kissing her with great reverence and a joyful countenance, and led her to her chamber, the officers of arms going before. After which every man went to his lodging, except certain noblemen and officers in waiting. The King and Queen went to supper, and "after super ther was sumptuus void."

On Friday, 30 May, all noblemen, &c. repaired to Court, and in a long chamber within the Tower were ordained 18 "baynes," in which were 18 noblemen all that night, who received the order of knighthood on Saturday, Whitsun eve. Also there were 63 knights made with the sword in honor of the coronation. Then all the nobles, knights, squires, and gentlemen were warned to attend on horseback, on the Tower Hill on Saturday next, to accompany her Grace to Westminster, to do service at the coronation."

Charles V. to his Ambassador at Rome.

Informs him of what has been discussed in his Council, in order that the same points may be laid before an assembly of councillors and advocates of the Queen. The best method of executing prompt justice was also to be discussed. Wishes the interdict to be the extreme penalty, as the people of England would not dare to observe it, and most of the people are opposed to the divorce, and should not suffer. Then again his subjects in the Netherlands would be injured, as no commerce is allowed with a people under interdict.

1534-Sir Thomas. More to Margaret Roper.

Prefatory Note by Editor of More's English Works.—Within a while after Sir Thos. More was in prison in the Tower, his daughter, Mrs. Margaret Roper, wrote and sent unto him a letter, wherein she seemed somewhat to labor to persuade him to take the oath (though she nothing so thought), to win thereby credence with Mr. Thomas Cromwell, that she might the rather get liberty to have free resort unto her father (which she only had for the most time of his imprisonment), unto which letter her father wrote an answer, the copy whereof here followeth:—

The terrible things he hears about himself are not so grievous to him as her letter trying to persuade him to the thing-wherein of pure necessity, for respect unto his own soul, he has often given her precise answer before. To the points of her letter can make no answer, having sundry times told her that he will disclose to no one the matters which move his conscience. Desires her to leave off such labor and be content with her former answers. A greater grief than the fear of his own death is that he hears that her husband, herself, his wife, and other children and friends are in danger of harm. Can only commit all to God, whom he prays to incline the King's heart to favor them all, and himself no better than his faithful heart to his Highness deserves. If the King could see his true mind as God knows it, it would soon assuage his high displeasure. Can never show it in this world but that the King may be persuaded to believe the contrary, and must put all in the hands of Him for fear of whose displeasure he suffers this trouble, out of which he prays God to bring him, when His will shall be, into the endless bliss of Heaven, and meanwhile to give him and her grace, in their agonies and troubles, to resort prostrate unto the remembrance of the Saviour's bitter agony.

Margaret Roper to Sir Thomas. More.

Note by Editor.—To this last letter Mrs. Margaret Roper wrote an answer and sent it to Sir Thos. More, her father, the copy whereof here followeth:—

It is no little comfort, since she cannot talk with him by such means as she would, to delight herself in this bitter time of his absence by often writing to him and reading his most fruitful and delectable letter, the faithful messenger of his virtuous and ghostly mind. Doubts not that God holds His holy hand over him, and will preserve him, both body and soul, now when he has abjected all earthly consolations and resigned himself to His holy protection. Their comfort since his departure has been their experience of his past life and godly conversation, wholesome counsel and virtuous example, and a surety of a great increase thereof.

Prays that God will help them to follow what they praise in him. “Your own most loving obedient daughter and bedeswoman, Margaret Roper, which desireth above all worldly things to be in John a Woods's stead, to do you some service. But we live in hope that we shall shortly receive you again. I pray God heartily we may, if it be His holy will.

Thomas More to all his Friends.

Being in prison, and not knowing what need he may have or what necessity he may be in, begs the*** all that if Margaret Roper, who alone has the King's licence to resort to him, desires anything of them that he may happen to need, they will regard it as if he asked it personally. Begs them to pray for him, and he will pray for them.

1536- Jane Boleyn, widow of Lord Rochford, to Cromwell

Beseeching him to obtain from the King for her the stuff and plate of her husband. The King and her father paid 2,000 marks for her jointure to the earl of Wyltchere, and she is only assured of 100 marks during the Earl's life, "which is very hard for me to shift the world withal." Prays him to inform the King of this.

1590 – Birth of Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, daughter of Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk, and his second wife, Katherine Knyvett.She was an English noblewoman who was the central figure in a famous scandal and murder during the reign of King James I. She was found guilty but spared execution, and was eventually pardoned by the King and released from the Tower of London in early 1622.

1621-Sir Francis Bacon was imprisoned in the Tower for four days on charges of accepting bribes and impeachment whilst he held political office.

source:http://www.mylifeatthetoweroflondon.com/,http://www.british-history.ac.uk/,wikipedia

-

30 May 1416-Jerome of Prague is burned as a heretic by the Church.He was a Czech church reformer and one of the chief followers of Jan Hus who was burned for heresy at the Council of Constance.

1431-Joan of Arc is burned at the stake by the English.

1472 – Death of Jaquetta de Luxembourg, Duchess of Bedford, Countess Rivers and mother of Elizabeth Woodville. She was the elder daughter of Peter I, Count of Saint-Pol, Conversano and Brienne and his wife Margaret de Baux (Margherita del Balzo of Andria). She was a relatively long-lived figure in the Wars of the Roses. Through her short-lived first marriage to the Duke of Bedford, brother of King Henry V, she was firmly allied to the House of Lancaster. However, following the emphatic Lancastrian defeat at the Battle of Towton she sided closely with the House of York. Three years after the battle and the accession of Edward IV of England, her eldest daughter Elizabeth Woodville married the new King to become his Queen Consort. Jacquetta bore 14 children (all with her second husband) and withstood a trial or possibly two at court for witchcraft.

1509-Bond of Francesco Grimaldi, Luigi de Vivaldo and Dominico Lomelyn for 45,000 ducats on account of the dower of Princess Katharine of Aragon. London, 30 May, 1509.

1519-Sir Thomas Boleyn to Henry VIII.

Immediately on hearing his pleasure, ordered Anthony Browne the bearer and Percival Hart to prepare themselves to go to England. Went with them to the King to take leave. He received them kindly, and said he had appointed them gentlemen of his house, and they should have the usual wages, 200 crs. a year. At their departure they received a whole year's wages, and their place and wages will be kept for them whenever they return. Browne has demeaned himself very well, and given good attendance, whereby he is much esteemed here. Writes more at length of other affairs to the Legate. Poissy, 30 May.

1525 – Wolsey proclaimed the King’s pardon for the rebels involved in the Amicable Grant Rebellion.

1529 - The Court at Blackfriars opened

Receipt by Stephen Gardiner and Peter Vannes of 3,000 g. cr. of the sun from Ansaldo de Grimaldis, merchant of Genoa, for the King's service, on letters of credit from D. Jo. Joachin sent from Venice; of which sum Gardiner received 1,500 cr., and 1,500 cr. were retained by Vannes partly on account and partly to despatch bulls. 30 May 1529.

1530-Croke to Henry VIII

In addition to the number mentioned in his last letters, has obtained the signatures of 18 doctors to the assertion of the conclusion, which he encloses with their names. Sends also extracts from the bishop of Worcester's letters, showing the advice received from him at different times in the King's name. Has not followed it altogether, for fear of rumor. Has treated of the King's causes only with father Franciscus Georgius, Joannes Franciscus Marinus, Thomas Omnibonus, and Simon Ardeus, otherwise called Simonetus, whose letters to the King he gave to the bishop of London on 15 May. Has been present, though unknown, when many doctors signed, and saw that only fear of the Pope prevented many from speaking and writing according to their learning and conscience. Doubted the Pope's granting open licence to speak freely, from his fear of the Emperor; and therefore asked the bishop of London to cause Ghinucci to tell the friars that the Pope wished every man to write and speak freely, if any question was put to them concerning matrimony in the behalf of the king of England, and that he should write that he had spoken with the Pope and perfectly knew his mind. If he did this, and leave was obtained from the Senate, would have no doubt of obtaining most of Italy, for the auditor Cameræ Apostolicæ is held in high estimation. Padua, 30 May.

1533 - Anne Boleyn begins her procession from the Tower to Whitehall Palace for her coronation

1536 - Marriage of King Henry VIII and Jane Seymour

1555 - Burnings of Protestant martyrs John Cardmaker and John Warne at Smithfield.

1574 - Death of Charles IX, King of France

1574 – Henry III becomes King of France.

1582 - Executions of Jesuit priest Thomas Cottam at Tyburn.

1588 – The last ship of the Spanish Armada sets sail from Lisbon heading for the English Channel.

1593 - Death of Christopher Marlowe, playwright and poet. He was stabbed to death at a house in Deptford Strand, near London.

source:http://www.onthisdayintudorhistory.com/,http://www.british-history.ac.uk/